Outdoor Skills for the Great Indoors

We all find ourselves in the midst of a new adventure, navigating through unknown terrain, scrambling for plans B,C, and D, when A went out the window.

We find ourselves with limited resources, isolated and afraid, frustrated and disappointed, unsure of what lies beyond this moment. We find ourselves, in other words, in the position that outdoor enthusiasts have found themselves since the dawn of time.

We may be stuck inside, confined to the indoors, but that doesn’t mean we can’t transfer what we’ve learned in our outdoor pursuits to handling a Shelter-In-Place order in light of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

4th graders prepare for their first backpacking trip, fall 2018

Grieving the Loss of “The Plan”

I had just finished an epic Costco food shop for my upcoming hut trip with my 4th graders when I got the call that all fieldwork was suspended indefinitely because of COVID-19. My shoulders slumped, I vented to my roommates for a few minutes, and then I knew I needed to let it go.

If there is any skill that is important in the outdoors, or as a leader in general, it is the ability to be flexible, adaptable, and creative. Things rarely ever go to plan, and so getting overly attached buys you a seat on the express train to suffering. As I stared at burrito ingredients for sixteen people, I thought of all the other times I’d been in similar positions and had to pivot. Three years before, when, ready to start 2 weeks on the Colorado Trail, we realized at the trailhead that we only had 5 shoes between 6 feet, leading to us cutting overall mileage and starting in a completely different location once we’d solved the mystery of the missing shoe.

And, how at the end of that trip, as thunderstorms began to show up regularly at 11am, we scrapped our plan to finish up in two days, each with moderate mileage, and hiked all 23 miles to the Western Terminus in one go. I remembered seven years ago, when my best friend and I sat in our tents in the pouring rain in Patagonia, with Cerro Torre completely invisible, despite the fact that we had come thousands of miles and this was our only shot on the trip to see it.

We are all grieving the loss of whatever plans we had for this period of time. School, jobs, vacations, fieldwork, celebrations, gatherings, events, adventures. It’s okay to be frustrated, but it’s also important to remember that plans are part of a nebulous future that was never promised to us, and we can either sit and be upset that our friend somehow lost their shoe, or the thing we came to see is socked in, or we can adjust, adapt, and move forward in the only reality that exists.

1. Overcast skies, Colorado Trail 2. The last few moments outside before a 12-hour thunderstorm, Colorado Trail 3. Navigation, Colorado Trail 4. Downtime after a long day of hiking, Colorado Trail

Existing in Confined Spaces

When I was 22, I spent three months in the wilderness of New Zealand’s South Island with the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS). During our month-long mountaineering section, we hit a period of three days where the weather was so bad up in the alpine that we could not leave our tent. We spent days laying around trying not to lose our minds from boredom, and nights sitting up and bracing the tent against the wind, getting out every hour to re-tie the guy lines so they wouldn’t snap. Over the course of those days, we napped, obsessively organized the gear in our packs, stared at the ceiling, planned out our next meal aggressively early, finished all the books we’d brought, and talked endlessly about life outside of this tiny space.

I look back at this moment now and the hours that seemed so long feel like a blur, and I mostly remember how good it felt to step out into the sunshine and walk up into the mountains a few days later, how that downtime was when I established strong friendships that still continue years later, and how I pushed myself to do something I wasn’t sure I could.

Anyone who spends any significant time in the mountains will inevitably find themselves stuck in a tent due to weather for more time than they would like, and must hone the skills required to do this while maintaining sanity. Keeping the space organized and clean, coming up with ways to entertain oneself, and maintain the firm belief that it will someday soon be over. Eventually, the weather would pass. Eventually, we’d be able to move. Eventually, we’d be able to continue on as planned. But not at this moment. At this moment, we had only one real thing to do: wait.

Right now, we can’t change the weather. We can’t speed this up. All we can do is embrace the confinement–find ways to make it clean, and comfortable, and beautiful, and find ways to entertain ourselves.

1. Inclement weather, Arrowsmith Range, New Zealand 2. Base camp before postholing up the Ashburton Glacier, New Zealand

Bonding with Others in Hyper-Speed

On extended stints in the backcountry, or long periods of travel, the people we’re with can begin to become our entire world. This can manifest itself in incredibly strong friendships that seem to solidify on a much quicker timeline than in “regular life.”

Last summer, I spent three weeks backpacking in Wyoming on a NOLS Outdoor Educator course. We traveled over 75 miles on and off trail through the Absarokas (pronounced Ab-sor-kas by locals), a much less frequented range than the neighboring Tetons and Wind Rivers, and saw only a handful of other people the entire time. The 12 of us started the course as strangers, and by only a few days in had started to speak in an invented shorthand that only made sense to us. We had nicknames for every piece of gear we brought, found ourselves heavily relying on gratuitous three-letter acronyms, and laughed heartily at inside jokes certainly only we thought were funny.

We became close in a very short time, due to each other’s constant presence, the lack of any outside interaction, and the common experience we were sharing. We laughed, we cried, we knew each other’s histories and secrets, recognized each other’s strengths and weaknesses, could predict each other’s reactions to things based on our personalities. Three weeks, in that setting, felt like three years.

We are all, at this point, holed up with the people we live with, and are inevitably having to navigate our relationships with those people in a new, much closer way. Experiencing this piece of history with these people is something that will always be a part of our stories, and we will inevitably find ourselves getting to a whole new level of weird with these people. Embrace the bonding!

1. Huddling under the tarp during a storm in the Absaroka Range, WY, summer 2019 2. Route planning while getting eaten alive by mosquitos in the Absarokas, WY

Managing Conflict in Confinement

In the year after I graduated from college, I spent a month traveling in South America with my best friend from college, prior to starting my first teaching job at a middle school in the Atacama Desert, Chile. Marielle and I came into the trip with different skill sets, backgrounds, and personalities, but had been close friends for four years, and felt unconcerned about how the trip would go. Marielle was organized, thorough, and detail oriented (she is now a doctor), and I was fluent in Spanish, familiar with South America, and enthusiastic. What could go wrong?

We soon realized that traveling together for an entire month without any other companions was a whole level of friendship that we hadn’t yet experienced. Inevitably, we got irritated with each other’s idiosyncrasies, ways of doing things, flaws, habits, etc. In a normal setting, when you’re frustrated with someone, you can take some space from them. In our situation, there was nowhere to go.

Being twenty-three, we decided to not address these issues throughout most of the trip, until finally things boiled over in our last few days together. We realized that without open and honest communication about how we were feeling and what we needed, we were going to drive each other nuts.

Part of the closeness of being with the same people all the time is the inevitable frustrations and conflicts that will arise, and we can all do ourselves a favor by working through them explicitly, and advocating for what we need. It’s good practice to do this all the time, but particularly when in confined spaces with others for extended periods of time.

Lots of tent time, Absaroka Range, WY

Rationing

A few days into quarantine, as my roommates and I did a full survey of the food in the house, we all started laughing at the familiarity of the situation we found ourselves in. We are all outdoor educators who have spent large periods of time in the backcountry, and realized immediately that the type of food that you can stockpile in a scenario like this one is pretty much backpacking food. Cheese and carbs? Oatmeal? Bars? Beans and rice? It brought us all back to the many summers we’d spent leading trips for teenagers, surviving for weeks off of food just like this. We are all avid plant-eaters, but have the ability to subsist off of granola bars and mac & cheese because of years of having to do it outside.

Backpacking also prepares you well for rationing–understanding that there is a limited quantity of food for a given amount of time, and that if you don’t properly plan out your meals, you will end up suffering. When on a long backpacking trip, you have to re-ration, whether by leaving yourself a box at a designated location like we did on the Colorado Trail, or by getting a food drop by car, horsepacker, or helicopter, like we did in Wyoming and New Zealand. You have those designated, infrequent times where you’re getting more food, and in between, you have to make what you’ve got last, which feels pretty similar to trying to minimize grocery store trips right now. This can mean portion control, planning out meals carefully based on what you have, and limiting yourself to a certain amount of something each day (1 bar a day, 1 packet of oatmeal or hot cocoa a day, etc.)

Helicopter re-ration, Arrowsmith Range, New Zealand

Facing Uncertainty

When I started on the Colorado Trail in 2017, I was coming off a minor-but-not-so-minor knee injury from a few weeks before. I’d hyperextended it after slipping on wet grass at my summer job leading trips, and wasn’t sure how I’d fare putting in multi-digit miles each day with a heavy pack. My friends and I had been planning this trip for almost a year–I’d spent countless hours nerding out on food, daily mileage, camping locations, and gear–and I felt intent on at least giving it a shot.

I began the trip with almost crippling uncertainty about how my body would hold up–would I be in pain the whole time? Would I be making the injury worse? Would I have to bail early? Would I ruin the trip for everyone?

I woke up each day, and frankly took each step, unclear on how it would all pan out. I wanted to feel the joy and peace I usually felt while out backpacking, but couldn’t erase the nervousness that came along with not being sure how it would go.

I began, instead of looking at the entire trip as a unit, to focus only on the smallest chunks I possibly could, and to spend intentional time taking care of myself. I didn’t think about hiking 130 miles all the way to Durango, I thought about getting to the top of the next pass. I thought about getting to our campsite for the night and putting my leg in the icy river for a few minutes. I thought about taking some weight from my friend Julianna’s pack, who was having trouble with her Achilles.

If we think about the expanse of this new normal laid out ahead of us, uncertain when it will end and how bad it will get and what will happen, it’s enough to make anyone hide under the covers. We can instead focus on smaller milestones–what are we doing today? How are we taking care of ourselves? How are we supporting others? We don’t know how it will all end up–no one has those answers for us–but we can take it one step at a time.

Enduring Unpleasant Circumstances

Being outside teaches us how to handle being uncomfortable, and then continue to do so long past the point where we decided we were over it. That’s what endurance is, really–can you just keep going? Keep moving? Keep managing? The outdoors ask us to endure an incredible amount– pain, exhaustion, inclement weather, elevation gain, filth, lack of resources, insects– the list goes on.

A classic scenario I’ve found myself in countless times is telling stories among a group of outdoor folks where each person is retelling the most heinously uncomfortable situation they’ve been in as if it were a) hilarious, and b) medal-worthy. The most uncomfortable times tend to make the best stories, tend to be the things we remember.

I think back to post-holing uphill to my hip in slush carrying a 60 pound backpack and bushwacking through thorned vegetation for hours in New Zealand; to waking up in a tent filled with water at 4am to start hiking 23 miles to the end of the Colorado Trail; to having blistered, soggy feet after doing multiple river crossings a day and getting incessantly harassed by mosquitos in Wyoming; to spilling all our pasta on the ground in Patagonia and having to pick it up out of the dirt and eat it anyway because it was our only food–the list goes on. Enduring circumstances like these is just part of the game when you’re outside.

We’re all having to endure different kinds of circumstances at the moment–stillness, stagnation, staying inside–but the ability to endure something that is not your first choice (or even your fifth) is a skill that we can all employ in this moment–the knowledge that you can survive the discomfort, that you can make it through, that it will end at some point, but until it does, you’ll continue.

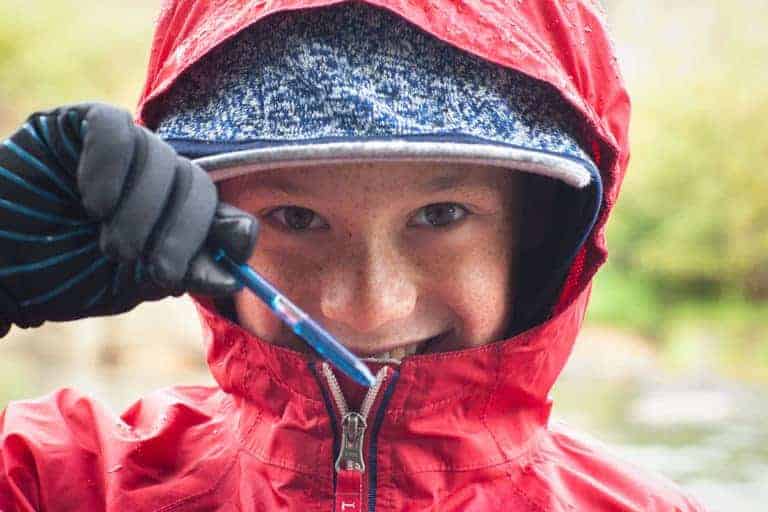

1. Waking up to snow on day 3 of the backpacking trip, Rubicon Trail 2019 2. 5th-grader setting up camp in Yosemite National Park, Fall 2018 3. 4th graders backpacking through the rain, Rubicon Trail 2019

Maintaining a Positive Attitude

Last spring, I woke up to one of the least friendly sounds a backpacker can hear–the pitter-pat of rain on my tent. It was day two of a three-day backpacking trip with my 4th graders, and we were starting the day off with rain. It’s rare that anyone is ever stoked that it’s raining on a multi-day trip, even seasoned adults, but I knew that my attitude would affect the kids’ attitudes, which would in turn, determine the entire day ahead of us.

I always tell my students that there are many things in life that we can’t control, but we can always control our responses, attitudes, and actions. We couldn’t control the fact that it was raining, but we could let that ruin our day, or not. After breakfast, I gathered the troops, and gave my best rousing pep talk about how the worse the conditions are, the greater the opportunity for learning & growth.

We put on our raingear and our pack covers, and headed out on the trail.

We spent the day walking through mud, crossing streams, and getting wet, but kept focusing on how the weather was making this much more of an adventure.

Would it have been nicer and easier if it were sunny and warm? Certainly. But would it be a better story, would we remember it more clearly, would it build up our confidence in ourselves more now that it was rainy and cold? Also, certainly.

We finished the third and final day of the trip in heavy snow, walking the final uphill miles to where the bus would pick us up, and the first students to arrive created a human tunnel for everyone else to run through, whooping and cheering and celebrating having accomplished this impressive feat.

We can’t control this virus, or the havoc it’s wreaking with our plans or our lives, but we can decide the attitude we adopt in the face of it. We can decide to look for the beauty, we can decide to embrace the growth, we can decide to smile anyway.